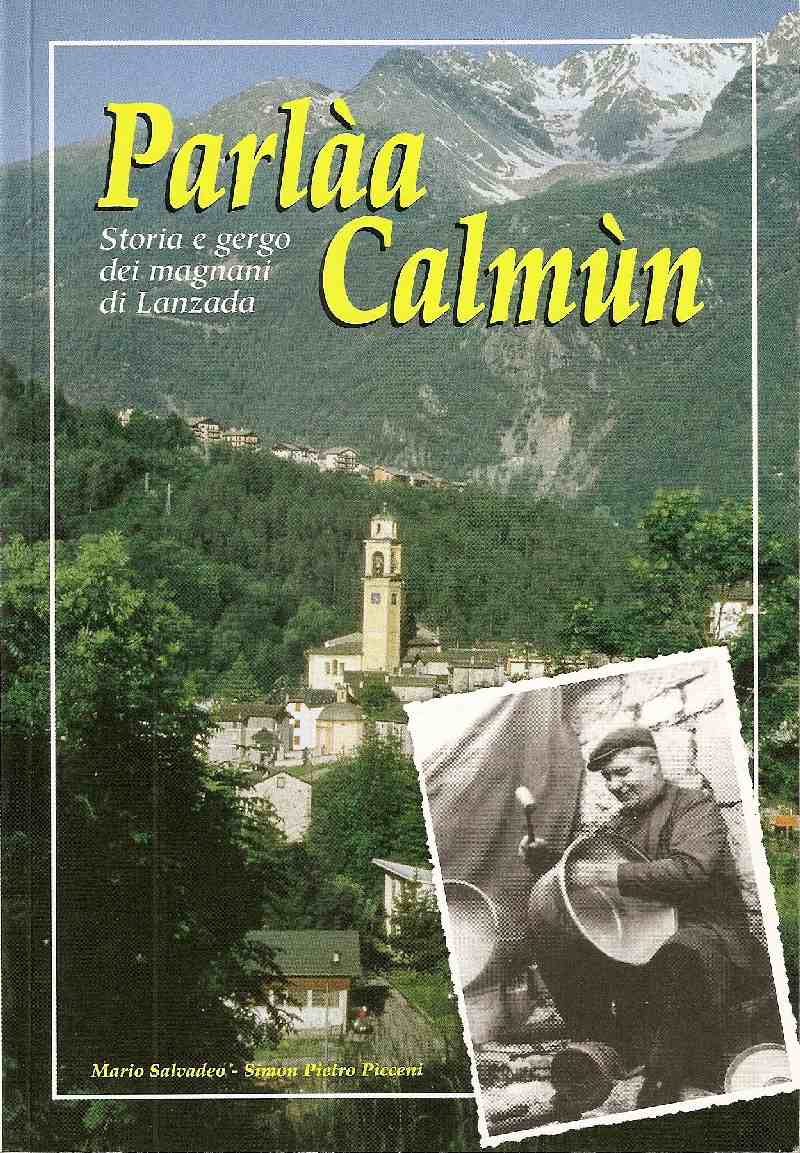

Title page of the volume published in 1998 on the Calmùn of Lanzada.

Title page of the volume published in 1998 on the Calmùn of Lanzada.

In Lanzada, the arrival and increase in the activity of the street tinsmith, the

(magnàn), gave rise to a slang known as

calmùn, of which traces remain today in the local dialect.

This language was used first and foremost by the

magnàn to communicate with each other without strangers understanding what they were saying.

It was a means of defence, which created a sort of solidarity within their group and also served as an easy trick to get out of complicated or embarassing situations.

The origin of the slang

calmùn, common to many street traders, can be found in a process of omosis between other languages in the common meeting places for travelling tradesmen in the street, the squares, the inns, etc.

In Italian, the word "calmone" means “to speak ambiguously”, “to speak in metaphors”, “to speak in slang”.

The word originally comes from the Greek

kalamos and from the Latin

calamos, and was used to signify arrow, dart and figuratively a sarcastic saying, a cutting remark (Tiraboschi).

In fact, slang is usually a way of making fun of strangers, a joke, a prank.

Some people, however, say it derives from "calmo", from the Latin

carmen, or as a group of words, of “magic”, of “sorcery”.

From here, Italian slang became "fascination", "deception etc.

As a result,

calmùn was said to be a secret language, with a certain fascination about it that served to deceive the person spoken to and to make fun of him” (Lurati).

Whatever the origin of the word, the

calmùn of the tinsmiths of Lanzada continued to acquire numerous words from Latin and from Italian, and at the same time picked up words of Greek, Spanish, French, German, English and Slavonic origin.

Here are a few interesting examples:

-

smèser (knife in calmùn) – Messer (knife in German)

-

slòfen (to sleep in calmùn) – schlafen (to sleep in German)

-

bula (town in calmùn) – boule (ancient Greek council)

-

valopp (letter in calmùn) – enveloppe (envelope in French)

The tinsmiths of Lanzada used their slang almost exclusively outside the village and when practising their trade.

In the later decades, when the work of the tinsmith began to diminish, speaking in slang

(plutunàa la calma), sometimes became a fashion and an instrument to make oneself appear eccentric.

After the war, slang was used by many of the labourers of Lanzada working in the mines and quarries, in the large, hydroelectric construction sites and by many people from the village who had emigrated to nearby Switzerland: they often used

calmùn to speak between themselves, to establish bonds of solidarity and sometimes of complicity between fellow villagers.

Bibliography

-

Ottavio Lurati,

L’ultimo laveggiaio della Valmalenco,

Tirano 1979

-

Simon Pietro Picceni - Giuseppe Bergomi - Annibale Masa,

Inventario dei toponimi valtellinesi e valchiavennaschi. 21 Territorio comunale di Lanzada,

Società Storica Valtellinese, Villa di Tirano, 1994

-

Mario Salvadeo – Simon Pietro Picceni,

Parlàa Calmùn. Storia e gergo dei magnani di Lanzada,

Sondrio 1998

-

Antonio Tiraboschi,

Vocabolario dei dialetti antichi e moderni,

Bergamo 1873