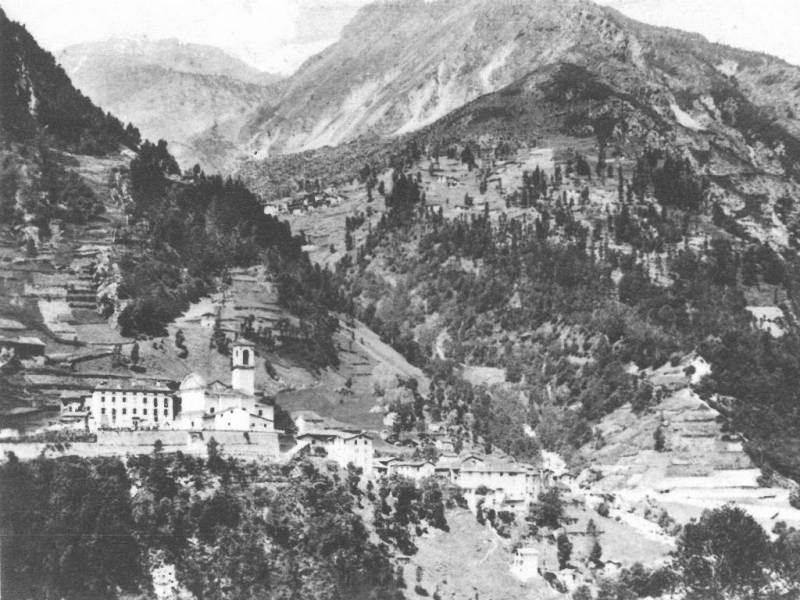

Terracing behind the district of Vassalini in Chiesa in Valmalenco.

Terracing behind the district of Vassalini in Chiesa in Valmalenco.

The technique of terracing is very common in the Valtellina and is one of the most significant examples of man's influence on the landscape.

A “Cyclopean work” which has enabled incredibly steep land to be dug and cultivated, thanks to a constant, obstinate desire to live on the Alpine slopes.

In the case of the Valmalenco we can rightly say that there was no alternative, given the steep area which forced the early inhabitants to work the craggy slopes of the valley with great difficulty.

They often faced bare rock worn smooth by the glacier and brought soil from below, which they supported by building dry stone walls.

The area exploited most using this technique was the one next to the municipality of

Spriana, although nowadays it is impossible to see any traces while travelling along the provincial road of the Valmalenco, on the opposite bank of the Mallero torrent.

Since part of the municipality was evacuated as a result of the landslide, the wood has expanded to such an extent and the old districts can be barely glimpsed through a thick layer of vegetation covering them almost completely.

Terracing in Lanzada.

Terracing in Lanzada.

However, a great deal of that area was "built" by man over the centuries using terracing.

As the slopes were so steep, it would have been unthinkable to cultivate without forming shelves, by building drystone walls and infilling with soil, which today give these mountain slopes their well-known steps.

Terracing was carried out wherever there was even a minimum amount of soil, and can be seen in the steep valley slopes and the rocky gorges, almost clinging to the impervious rocky crests.

They were even built above the larger outcrops, on which they created small patches of grass and vegetable patches, built various buildings and even the tiny church of the

Madonna della Speranza.

Until the fifties, they were still rationally exploiting and fertilising and scything the meadow.

The different coloured crops dominated the scene, long garlands of corn cobs hung from the balconies in the villages and farmyards were full of wheat sheaves.

The openings under the eaves were "walled" with logs and and the homes and fields and steep slopes were all swarming with people hard at work.

Terracing in Torre S. Maria.

Terracing in Torre S. Maria.

The other municipalities in the valley were no different to Spriana and their slopes were cultivated on top of drystone walls, most of which have unfortunately disappeared today: from Torre to Chiesa to Lanzada where they are still visible, although partially wooded, they are remarkable evidence of man's work.

They cultivated mainly cereals on the terracing in Valmalenco, which included rye,

doméga

(barley), oats, millet, panic grass, wheat, maize and potatoes.

Where they were unable to cultivate the land, they kept it as meadowland to provide hay for the animals.

The work of cultivating terraced fields was exhausting and often thankless, and demanded untiring physical effort.

Each spring, they had to replace the soil that had inevitably slid downwards.

In autumn, they usually had to shoulder the basket dripping with manure to be spread over the terraced fields.

Each year they had to dig the ground to prepare it for new sowing and to free it from a large quantity of stones, which continually rose to the surface.

These stones were then piled up to mark the boundaries of the different properties

(i gändi de sàas).

Bibliography

-

Dario Benetti,

A confine tra diverse culture: le tipologie delle dimore rurali in Valtellina e Valchiavenna, in

La dimora alpina, Atti del convegno di Varenna,

3-4 June 1995, pp. 307-332

-

Annibale Masa,

Inventario dei toponimi valtellinesi e valchiavennasch. 13 Territorio comunale di Spriana,

Società Storica Valtellinese, Sondrio 1982