Nicolò Rusca was born in 1563 in Bedano, in the Canton of Ticino.

He completed his priestly studies and was awarded a degree in theology at the Swiss College, established in Milan by the archbishop, Carlo Borromeo.

He was elected archpriest of Sondrio in 1590 and remained there for almost thirty years until his death (1618).

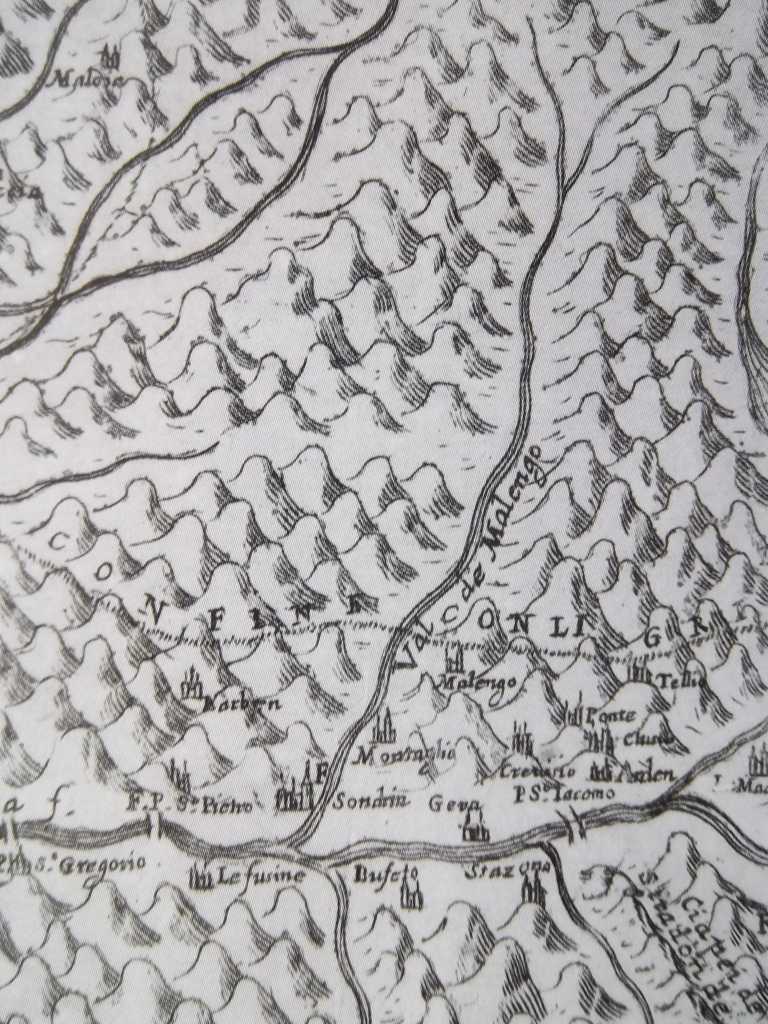

The true drawing of the Valtellina and Val Chiavenna with its borders, 1620 ca. Detail of the Val Malenco.

The true drawing of the Valtellina and Val Chiavenna with its borders, 1620 ca. Detail of the Val Malenco.

At that time, Sondrio was the geographical and administrative centre of the Valtellina which, from 1512, was subjected to the free State of the Three Leagues.

Between 1526 and 1527, the Reform had spread in the land of the Grigioni family with the emanation of the so-called edict of tollerance (Toleranzedict), which acknowledged the right to hold the reformed confession side by side with the Catholic confession.

In Valtellina and in Valchiavenna.

the spread of the Reform was rather restricted to a few communities compared to the catholic majority of the population.

However, the decrees of the Grigione government (1576) forced the communities to give their churches to the reformed congregations, or to share their use where there was only one church, and to share the expenses for the reformed preachers.

When Nicolò Rusca arrived in the parish of Sondrioas parish priest, he was faced with a a catholic community in decline and in spiritual crisis due mainly to the negligence of the clergy up to that point.

His pastoral work aimed, therefore, to improve the future of local Catholicism by putting into practice the principles for the renewal of the church, as dictated by the Council of Trent (training for the clergy and spiritual teaching for laymen) and, at the same time, curbing the spread of the protestant reform.

He was not alone in his pastoral work, but surrounded himself with a large group of young priests, with whom he implemented a vast project of reform, expressed mainly by preaching, teaching catechism to the children and by setting up a school of Christian doctrine for the adults.

He sent out well-prepared priests into the most disadvantaged communities in his parish, such as those of the Valmalenco.

In particular, he used those residing permanently in the villages, capable of ensuring the populations a liturgical and spiritual service.

With these priests and with many other priests of the Valtellina, he knew how to establish a network of friendship and collaboration in a climate of fraternity.

He was particularly committed to encouraging priestly vocation: he paid close attention to his relationship with the young men who had taken up the priesthood and he followed them with sincere, spiritual friendship and continual dialogue.

A figure with a deep cultural background and intense motivation for priestly duties, it was to Nicolò Rusca's credit that he was able to translate the theoretical principles of the Council of Trent into a language that was accessible to the local people.

By being the first to set an example, he represented the new model of a priest, who would take direct care of the community encharged to him, by ensuring a stable, assiduous presence amidst the people.

His untiring effort in defence of the catholic religion soon attracted the anger of the reformers who, after a while, could no longer put up with the success of his work to renew his religion.

His opposers denounced him several times, he was imprisoned and then acquitted (1608-10).

Considered a troublesome, formidable person, in 1618 he ended in the hands of an extremist, deeply anti-catholic, reformed group, which managed to build a totally unfounded accusation against him of betrayal of the State.

Captured between 24 and 25 July that year by an armed band of Grigioni, he was deported through the Valmalenco to Coira, and finally to Thusis, where he died under torture on 4 September 1618.