Orsatti's idea was very practical and well-thought out: to open a rail link with Engadine from the Valtellina, which would cross the deep valley of the Valmalenco, which “pushes forward like a wedge between the Swiss valleys of Poschiavo and Pregallia [Bregaglia, author's note]”

.

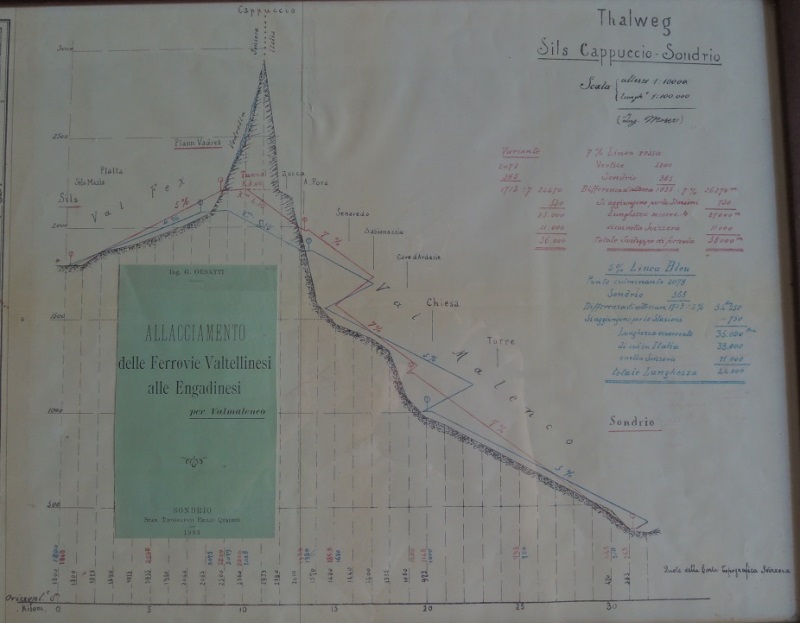

Orsatti's project envisaged two alternating tracks, stretching for a total of 54 km, 27 of which in the Valmalenco,

3 in tunnels under Pizzo Tremogge, 8 descents along the Val di Fex as far as Sils, and the remaining 16 (approximately 6 of which already had tracks) from Sils to Samaden, the main railway hub towards Lower Engadine and Coira.

According to the project designer, the crossing through the Valmalenco could even have been a threat to the supremacy of the

Gottardo as an international line “from Milan to Coira via Lake Constance”

, as the distance between Milan and Coira through the Valmalenco was a mere 272 km, to which the mandatory passing through the Gotthard tunnel added about another hundred.

Project "Link between the Valtellina Railways and the Engadine Railways via the Valmalenco"

Project "Link between the Valtellina Railways and the Engadine Railways via the Valmalenco"

Passing through the gentle pastures of San Giuseppe, the narrow gauge railway track,

to better adapt to the morphology of the valley and therefore save considerably on infrastructures,

was to climb as far as Entova, and then be swallowed by the mountain at Alpe di Fora and come out on the Swiss side at Plan Vadret.

The trains would have run on electricity “taken from the Mallero at a convenient spot, such as the quarries in Chiesa”

, to overcome inclines of up to 14% at an average speed of approximately 10 km per hour.

Alpe Fora, Piani di Fora and Pizzo Tremoggia

Alpe Fora, Piani di Fora and Pizzo Tremoggia

In his brief report, Orsatti enthusiastically calculated in detail the cost of the enterprise (which he worked out as LIRA 9 million).

He also provided the cost analysis to fund the project, which was to involve the State, local authorities (the provinces of

Sondrio, Bergamo, Brescia, Como and Milan), their respective chambers of commerce and private shareholders.

The prospect of great commerical and tourist advantages for the entire area, and especially for the Valtellina, should have encouraged the aforementioned organisations to take part in the enterprise.

The reciprocal economic benefits induced by this strategic itinerary were to fall equally on Italy and Switzerland:

“the initiative of our neighbours in Engadine will not be lacking (…) to add new landscapes for their 50,000 annual holidaymakers (…), to enjoy the waters of the Mallero, which can be transported through the tunnel (…) and to use the slates from Chiesa”

.

The main advantages for the people of the Valtellina consisted of the opportunity to easily export their wine,

the previously mentioned slates, soapstone, magnesite, talc and timber: the railway would also facilitate the flow of seasonal workers and cattle.

In addition to the commercial benefits, it would also have favoured the flow of tourists and made “the peaks of Disgrazia and Bernina more accessible to the less daring tourists”

.

It would also have launched the industry – already flourishing in Alto Adige – of the

traubenkur [ancient grape cure].