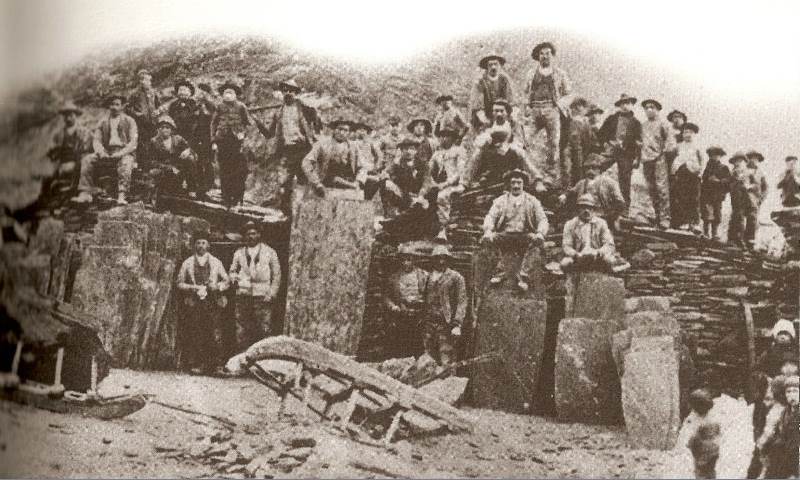

Giovellai [quarrymen] in the early 20th century.

Giovellai [quarrymen] in the early 20th century.

The landscape, as seen by a visitor to Chiesa Valmalenco a few centuries ago, would have been very different from today's and not just from a town planning point of view (a common aspect to many villages in the Alpine valleys), but more specifically from a strictly morphological viewpoint.

In fact, in ancient times, a natural wall of rock separated the fertile hollow of Chiesa from the higher pastures.

And up this wall climbed the

“Cavallera” road of the Muretto pass: a wall built in the shape of a yoke (1,140 m) and now almost completely demolished, later referred to as the

Giovello (little yoke).

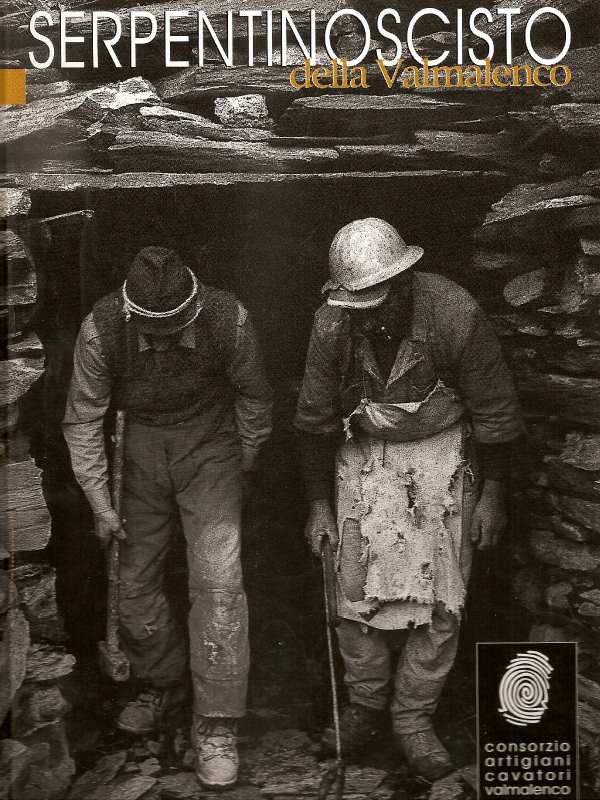

Title page of the volume edited by the consortium, Consorzio Artigiani Cavatori Valmalenco.

Title page of the volume edited by the consortium, Consorzio Artigiani Cavatori Valmalenco.

It was probably in the early centuries after the year one thousand that someone stopped during the tiring walk up or down and observed the layers of serpentine rock that appeared on the surface.

They were clearly in sheets and in some points seemed reduced to slivers.

Soon, the men of Chiesa, experts in excavating the local iron mines, attempted to split those layers, and realised how easily they could be split into sheets, which could be put to good use: for flooring in their mountain huts or better still for the roofing to replace the thatch and shingles which did not last long.

Those sheets were not only of a considerable size and characteristic appearance, they were also flat, thin, light, easy to transport, impermeable and, therefore, resistant to the lowest temperatures and shock and weather proof.

Their experience in extracting iron with the use of special tools and fire introduced into the rock to make cracks to remove it, led to the creation and evolution of the techniques to extract and process serpentine stone.

Quarryman at work.

Quarryman at work.

Track along which the càr ran to transport the blocks of serpentine stone.

Track along which the càr ran to transport the blocks of serpentine stone.