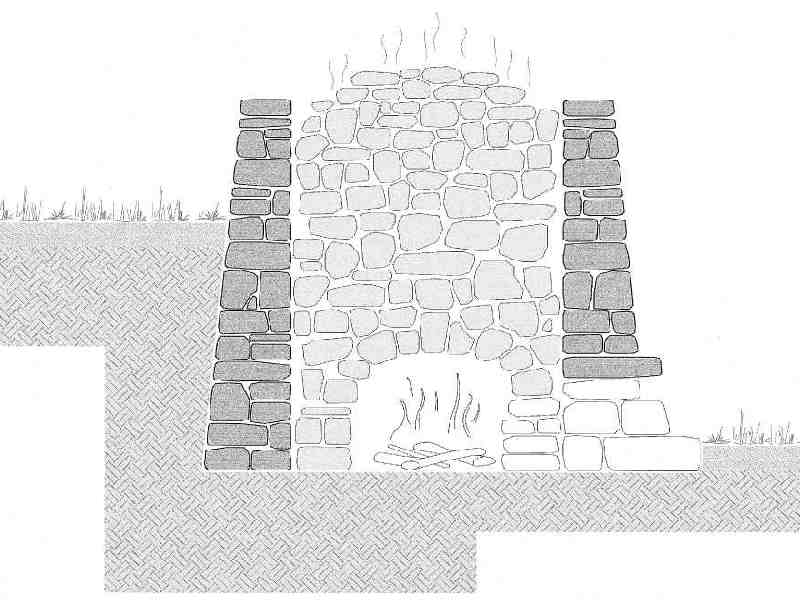

Section of a kiln.

Section of a kiln.

Around the inner circumference of the kiln, starting from the bottom, rose a

wall of evenly shaped lime stones, on which the domed top rested

(se fa l’vò); they continued to fill the kiln in this way and shut the dome with large stones.

In the

combustion oven they first gathered the bundles of sticks to be burnt, followed by logs

(se carga la furnàs) which blocked the entrance to the kiln and prevented heat from coming out.

A great deal of care and very little wood was required in the heating phase, in order not to spoil the product: the stone didn't have to blacken and they had to avoid the formation of a raw nucleus within the blocks of limestone.

Gradually the flames pentrated through the limestone block and reached the top of the kiln.

The fire was fed continually to give a slow, gradual combustion, sometimes up to 1,300°C for about eight or ten days.

They needed up to 200 quintals of wood to guarantee such a high temperature, which would yield approximately 120 quintals of quicklime.

At the end of the process, the green and yellow flames turned blue to show the calcium carbonate had transformed into calcium oxide (Ca0), or quicklime.

The stone had to be cooled slowly.

The top was protected with wooden boards to keep any sudden downpours away from the product.

The rock extracted from the kiln was lighter in colour and weighed thirty per cent less than it did originally.

The kiln was emptied by remove the rocks from the top to free the loading hole in the dome.

Limestone

Blocks of limestone.

Blocks of limestone.

Limestone is one of the most common, widespread, sedimentary rocks and consists of at least 50% calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

It is off-white in colour, but also has other shades if any mineral oxide impurities are present.

Nowadays, the marlstone or limestone containing suitable impurities in the right quantity is used to produce natural cement.

The people of the valley also used fragments of limestone in agriculture to correct the excessively acid soil.

Quicklime, mixed with copper sulphate was used against downy mildew on the vines.

Slaked limestone

Quicklime, if not used immediately, was kept in a dry place or was subjected to a process to slake it in ditches of water known as "slakers", which gave off a violent release of heat and disintegrated the stone.

Use of lime.

Use of lime.

This phase was in two parts: first, in an initial slake tank (a wooden box with high sides called

benèl de la calcina), then in maturing tanks dug in the ground, in which the slaked lime formed.

The mixture obtained in this way was mixed several times and could be kept for a long time by covering it with a layer of water to prevent it from drying out and altering.

Most of the lime was used to prepare mortar and binding agents for the construction industry.

Setting began by removing the water.

Then it dried as it came into contact with the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

This slow process retransformed the original compound into lime.

It was not only the mason who needed lime.

Every house in the countryside had a deep hole, prepared in the

nell’involt (cellar), which they filled with slaked lime and when it was needed, they used it

per dà ‘l bianc (to whitewash) the barns and the rooms, and a layer of lime plaster was laid as a disinfectant.