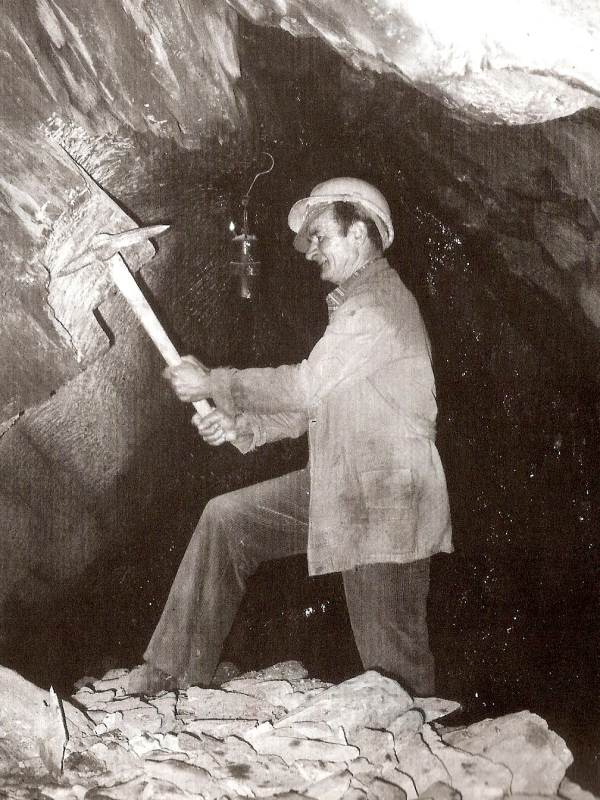

Soapstone quarryman at work.

Soapstone quarryman at work.

They used double-pointed pickaxes

(ascìsc) with wedges and mallets to excavate the schistose material and free the deep-lying seam of soapstone.

Freeing the stone

(liberà la préda) was long, hard work.

It took years to free the seam, from which they extracted the

ciapùn, truncated, conical-shaped blocks of stone, which they then used to make the cooking pots.

The tunnels in the oldest quarries were so narrow that the quarrymen had to bend down and move forward on all fours. They wore straw-padded cushions to protect their hips and shoulders.

They worked in the light of a sort of torch of resinous wood (made of cembran pine or mountain pine known as

löm).

Towards the end of the 19th century, it was replaced first with oil, followed by acetylene lamps.

As the quarries were very wet with running water, extraction only took place in winter, when the ice blocked every infiltration through the cracks in the rock.

After a day's work, the quarryman removed the

ciapùn from the rock, tearing it from the seam, and with great difficulty carried it to the entrance of the tunnel on his back or on a sort of sled

(tirùn) made with a forked branch of mountain pine.

From the second half of the last century, they began to use hammer drills to extract the soapstone in blocks weighing between five and ten quintals each.

They then used explosive powder to detach the block.